Scientists Build Synthetic Cells That Tell Time

Researchers at UC Merced have successfully created tiny artificial cells capable of keeping time with remarkable precision, closely resembling the natural daily cycles observed in living organisms. This discovery offers new insight into how biological clocks maintain accurate timing, even amid the random molecular fluctuations that occur within cells, the journal Nature Communications reported.

The study was led by bioengineering Professor Anand Bala Subramaniam and Professor Andy LiWang of the chemistry and biochemistry department. The lead author, Alexander Zhang Tu Li, completed his Ph.D. under Subramaniam’s guidance.

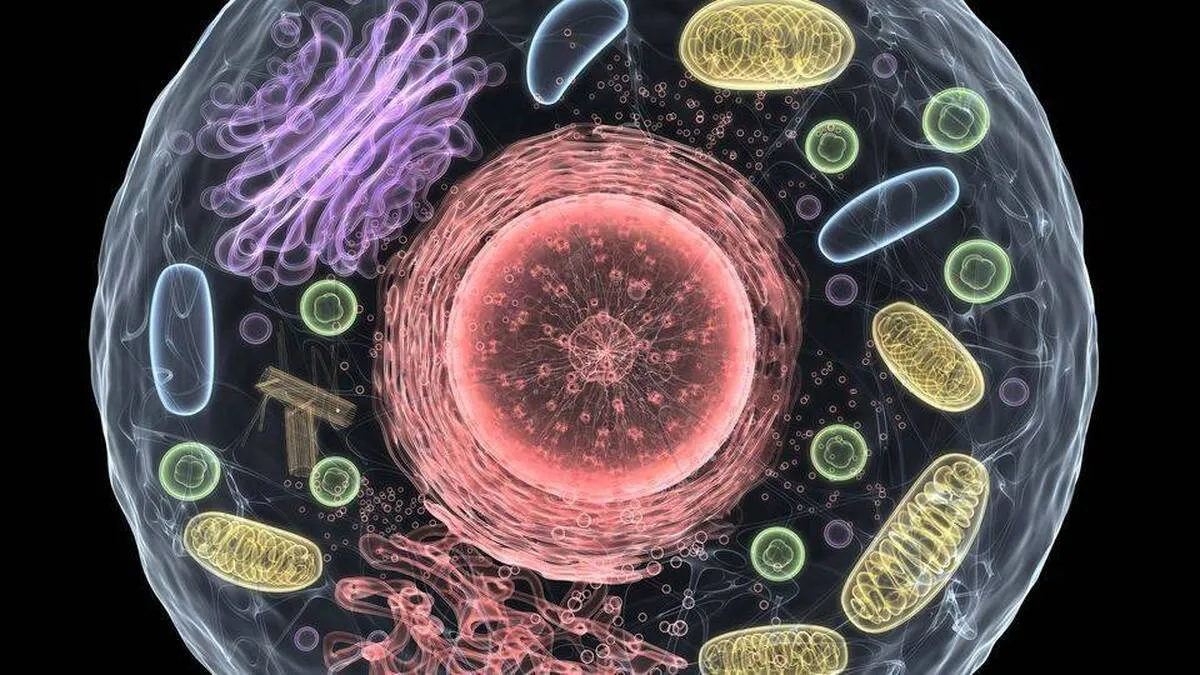

Biological clocks, commonly referred to as circadian rhythms, are internal systems that manage essential 24-hour cycles such as sleep, metabolism, and other key bodily functions. To better understand how these rhythms operate in cyanobacteria, the research team recreated the timing mechanism inside simplified, synthetic cell structures known as vesicles. These vesicles were filled with the core proteins that drive the biological clock, with one protein labeled using a fluorescent marker to make the timing activity visible.

The engineered cells emitted a consistent glowing signal that followed a 24-hour cycle for at least four days. When either the concentration of clock proteins was decreased or the vesicle size was reduced, the rhythmic glow disappeared. This disruption occurred in a consistent and predictable pattern.

To explain these findings, the team built a computational model. The model revealed that clocks become more robust with higher concentrations of clock proteins, allowing thousands of vesicles to keep time reliably — even when protein amounts vary slightly between vesicles.

The model also suggested another component of the natural circadian system — responsible for turning genes on and off — does not play a major role in maintaining individual clocks but is essential for synchronizing clock timing across a population.

The researchers also noted that some clock proteins tend to stick to the walls of the vesicles, meaning a high total protein count is necessary to maintain proper function.

“This study shows that we can dissect and understand the core principles of biological timekeeping using simplified, synthetic systems,” Subramaniam said.

The work led by Subramaniam and LiWang advances the methodology for studying biological clocks, said Mingxu Fang, a microbiology professor at Ohio State University and an expert in circadian clocks.

“The cyanobacterial circadian clock relies on slow biochemical reactions that are inherently noisy, and it has been proposed that high clock protein numbers are needed to buffer this noise,” Fang said. “This new study introduces a method to observe reconstituted clock reactions within size-adjustable vesicles that mimic cellular dimensions. This powerful tool enables direct testing of how and why organisms with different cell sizes may adopt distinct timing strategies, thereby deepening our understanding of biological timekeeping mechanisms across life forms.”

4155/v