Scientists Strip Cells of Mysterious Organelles to Reveal Hidden Secrets

Researchers at UT Southwestern Medical Center have employed a genetic method that compels cells to eliminate their mitochondria, providing new insight into the functions of these essential organelles. The results, published in Cell, contribute to a deeper understanding of how mitochondria operate within cells and across evolutionary history. This work also holds promise for developing future therapies for mitochondrial disorders such as Leigh syndrome and Kearns-Sayre syndrome, both of which can impact multiple organ systems.

“Our new tool allows us to study how changes in mitochondrial abundance and the mitochondrial genome affect cells and organisms,” said Jun Wu, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Molecular Biology at UT Southwestern. Dr. Wu co-led the study with Daniel Schmitz, Ph.D., a former graduate student in the Wu Lab who is now a postdoctoral fellow at the University of California, Berkeley.

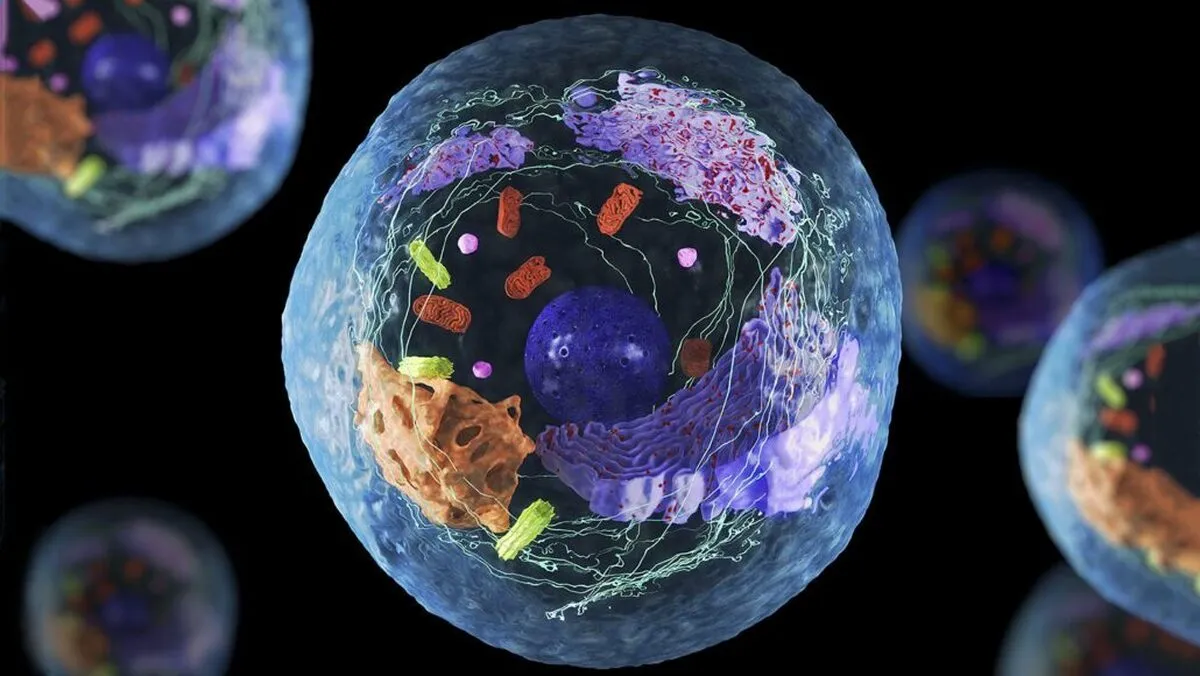

Mitochondria are specialized structures located within the cells of most eukaryotic organisms, such as animals, plants, and fungi. These cells are characterized by having a membrane-bound nucleus along with other enclosed organelles. Unique among cellular components, mitochondria contain their own DNA, which is inherited solely through the maternal line. Scientists believe that mitochondria evolved from ancient prokaryotic cells (which lack internal membranes) that entered primitive eukaryotic cells and established a mutually beneficial relationship.

Traditionally recognized for producing adenosine triphosphate—the molecule that supplies energy for nearly all cellular functions—mitochondria have also been found to play more complex roles. Recent research reveals they are involved in regulating cell death, guiding stem cells as they develop into specialized cell types, relaying molecular signals, influencing aging processes, and coordinating developmental timing.

Many of these functions are believed to rely on communication, or “crosstalk,” between mitochondrial DNA and the DNA in the cell’s nucleus. Yet the mechanisms behind this interaction, and the consequences of its disruption, remain largely unclear.

To investigate these unknowns, Dr. Wu, Dr. Schmitz, and their team utilized mitophagy, a natural cellular process that removes damaged or aging mitochondria. Through genetic engineering, they triggered cells to eliminate all of their mitochondria, a technique referred to as “enforced mitophagy.”

They applied this method to human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), which are early developmental cells capable of becoming various specialized cell types. While the complete loss of mitochondria halted the cells’ ability to divide, the researchers were surprised to discover that these cells remained viable in petri dishes for up to five days. Comparable outcomes were observed in both mouse stem cells and hPSCs carrying a harmful mitochondrial DNA mutation, indicating that enforced mitophagy may serve as a broadly applicable approach for removing mitochondria across different species and cell types.

To determine how removing mitochondria affected the hPSCs, the researchers assessed nuclear gene expression. They found that 788 genes became less active and 1,696 became more active. An analysis of the affected genes showed the hPSCs appeared to retain their ability to form other cell types and that they could partially compensate for the lack of mitochondria, with proteins encoded by nuclear genes taking over energy production and certain other functions typically performed by the missing organelles.

Then the researchers, in an attempt to better understand crosstalk between mitochondria and the cell nucleus, fused hPSCs with pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) from humans’ closest primate relatives – including chimpanzee, bonobo, gorilla, and orangutan. This formed “composite” cells with two nuclear genomes and two sets of mitochondria, one from each species. These composite cells selectively removed all non-human primate mitochondria, leaving behind only human mitochondria.

Next, using enforced mitophagy, the scientists created hPSCs devoid of human mitochondria and fused them to non-human primate PSCs, again creating cells carrying nuclear genomes from both species, but this time only non-human mitochondria. An analysis of composite cells containing either human or non-human mitochondria showed that the mitochondria were largely interchangeable despite millions of years of evolutionary separation, causing only subtle differences in gene expression within the composite nucleus.

Interestingly, the genes that differed in activity among cells harboring human and non-human mitochondria were mostly linked to brain development or neurological diseases. This raises the possibility that mitochondria may play a role in the brain differences between humans and our closest primate relatives. However, Dr. Wu said, more research, especially studies comparing neurons made from these composite PSCs, will be needed to better understand these differences.

Finally, the researchers studied how depleting mitochondria might affect development in whole organisms. They used a genetically encoded version of enforced mitophagy to reduce the amount of mitochondria in mouse embryos, then implanted them into surrogate mothers to develop. Embryos missing more than 65% of their mitochondria failed to implant in their surrogate’s uterus. However, those missing about a third of their mitochondria experienced delayed development, catching up to normal mitochondrial numbers and a typical developmental timeline by 12.5 days after fertilization.

Together, the researchers say, these results serve as starting points for new lines of research into the different roles mitochondria play in cellular function, tissues and organ development, aging, and species evolution. They plan to use enforced mitophagy to continue studying these organelles in a variety of capacities.

4155/v