‘Death Wish’ Planet Slowly Killing Itself

Astronomers working with the European Space Agency’s Cheops mission have observed an exoplanet that appears to be setting off powerful radiation flares from its host star. These intense bursts are stripping the planet’s thin atmosphere, gradually reducing its size each year, the journal Nature reported.

This marks the first direct evidence of a planet actively influencing its star in this way. Although scientists proposed this possibility in the 1990s, the flares detected in this study are about 100 times stronger than previously predicted.

Observations from telescopes like the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope and NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) had already provided early insights into the exoplanet and its parent star.

The star, HIP 67522, is slightly larger and cooler than our Sun, but significantly younger—just 17 million years old compared to the Sun’s 4.5 billion years. It hosts two known planets, the innermost of which, HIP 67522 b, completes an orbit in only seven days.

Due to the star’s young age and relatively large size, researchers anticipated that HIP 67522 would be highly active, with intense rotation and internal movement. These characteristics would make the star a strong generator of magnetic fields.

In contrast, the older Sun has a weaker and more stable magnetic field. Scientists already understand that in stars with magnetic fields, flares can erupt when tangled field lines snap and release energy. These outbursts can manifest as anything from soft radio emissions to bright visible light or even high-energy gamma rays.

Ever since the first exoplanet was discovered in the 1990s, astronomers have pondered whether some of them might be orbiting close enough to disturb their host stars’ magnetic fields. If so, they could be triggering flares.

A team led by Ekaterina Ilin at the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy (ASTRON) figured that with our current space telescopes, it was time to investigate this question further.

“We hadn’t seen any systems like HIP 67522 before; when the planet was found it was the youngest planet known to be orbiting its host star in less than 10 days,” says Ekaterina.

“We quickly requested observing time with Cheops, which can target individual stars on demand, ultra precisely,” says Ekaterina. “With Cheops, we saw more flares, taking the total count to 15, almost all coming in our direction as the planet transited in front of the star as seen from Earth.”

Because we are seeing the flares as the planet passes in front of the star, it is very likely that they are being triggered by the planet.

A flaring star is nothing new. Our own Sun regularly releases bursts of energy, which we experience on Earth as ‘space weather’ that causes auroras and can damage technology. But we’ve only ever seen this energy exchange as a one-way street from star to planet.

Given HIP 67522 b’s very tight orbit and the likely strength of its star’s magnetic field, Ekaterina’s team concluded that the planet is close enough to impact the star’s magnetic behavior.

They propose that as the planet moves through its orbit, it collects energy and sends it back as waves along the star’s magnetic field lines, much like the motion of a snapped rope. When these waves reach the ends of the magnetic field lines at the star’s surface, they release that energy in the form of powerful flares.

It’s the first time we see a planet influencing its host star, overturning our previous assumption that stars behave independently.

And not only is HIP 67522 b triggering flares, but it is also triggering them in its own direction. As a result, the planet experiences six times more radiation than it otherwise would.

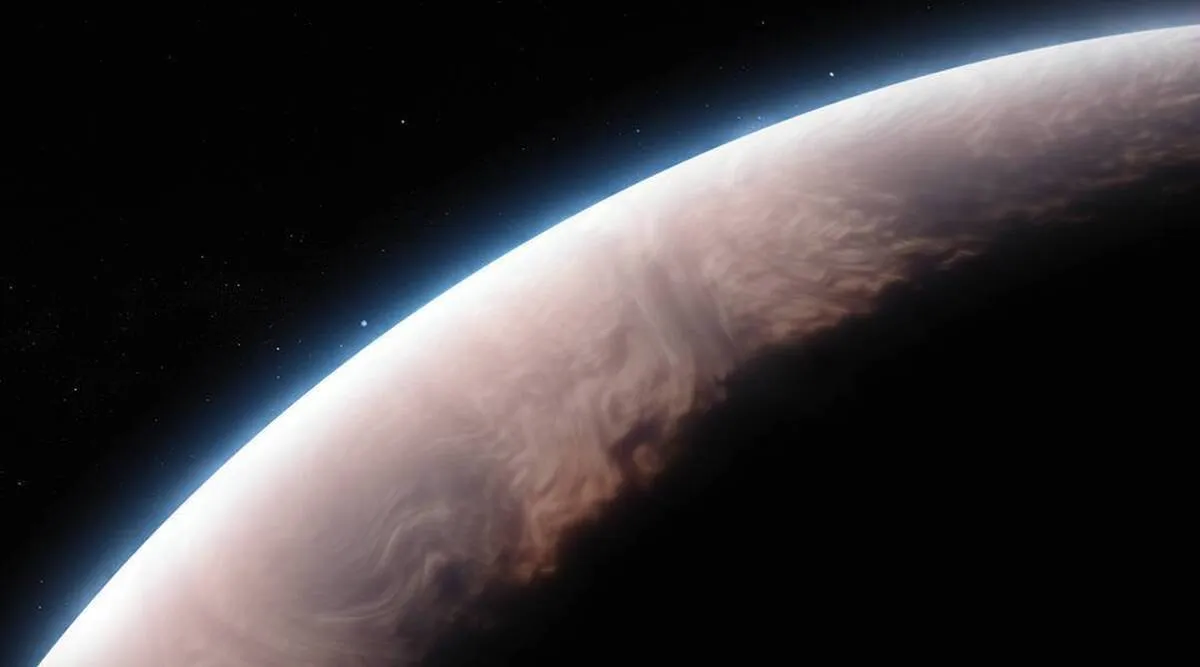

Unsurprisingly, being bombarded with so much high-energy radiation does not bode well for HIP 67522 b. The planet is similar in size to Jupiter but has the density of candy floss, making it one of the wispiest exoplanets ever found.

Over time, the radiation is eroding away the planet’s feathery atmosphere, meaning it is losing mass much faster than expected. In the next 100 million years, it could go from an almost Jupiter-sized planet to a much smaller Neptune-sized planet.

“The planet seems to be triggering particularly energetic flares,” points out Ekaterina. “The waves it sends along the star’s magnetic field lines kick off flares at specific moments. But the energy of the flares is much higher than the energy of the waves. We think that the waves are setting off explosions that are waiting to happen.”

When HIP 67522 was found, it was the youngest known planet orbiting so close to its host star. Since then, astronomers have spotted a couple of similar systems and there are probably dozens more in the nearby Universe. Ekaterina and her team are keen to take a closer look at these unique systems with TESS, Cheops, and other exoplanet missions.

“I have a million questions because this is a completely new phenomenon, so the details are still not clear,” she says.

“There are two things that I think are most important to do now. The first is to follow up in different wavelengths (Cheops covers visible to near-infrared wavelengths) to find out what kind of energy is being released in these flares – for example, ultraviolet and X-rays are especially bad news for the exoplanet.

“The second is to find and study other similar star-planet systems; by moving from a single case to a group of 10–100 systems, theoretical astronomers will have something to work with.”

Maximillian Günther, Cheops project scientist at ESA, is excited to see the mission contributing to research in a way that he never thought possible: “Cheops was designed to characterize the sizes and atmospheres of exoplanets, not to look for flares. It’s really beautiful to see the mission contributing to this and other results that go so far beyond what it was envisioned to do.”

Looking further ahead, ESA’s future exoplanet hunter Plato will also study Sun-like stars like HIP 67522. Plato will be able to capture much smaller flares to really give us the detail that we need to better understand what is going on.

4155/v