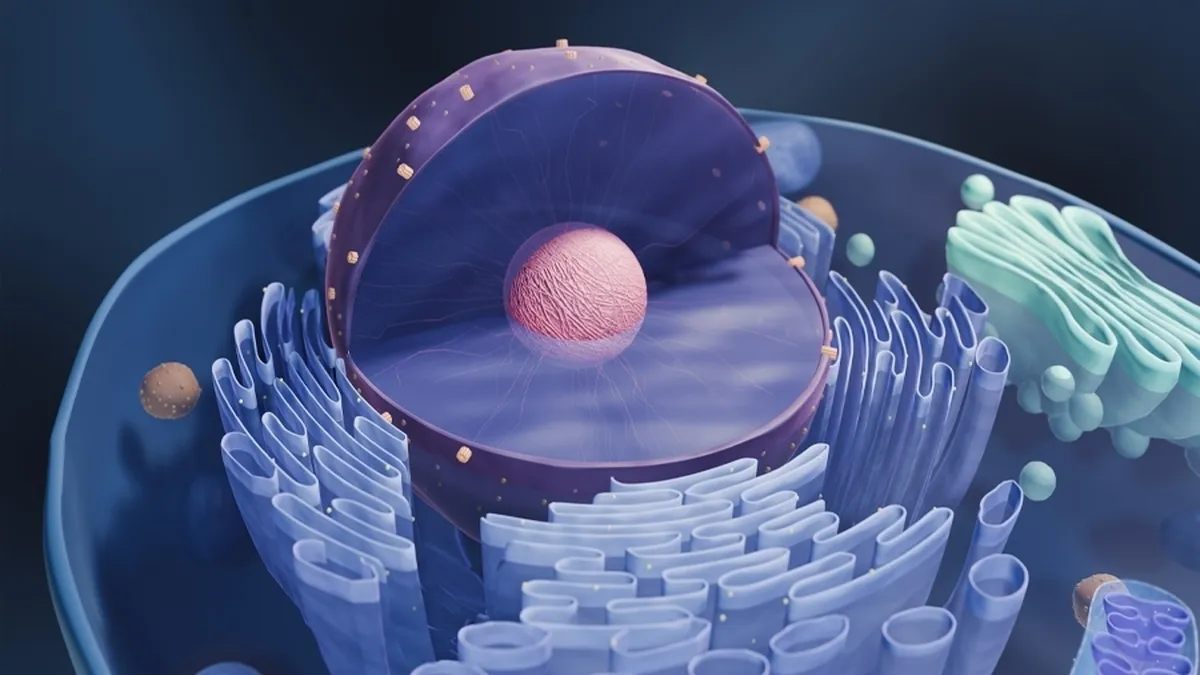

Scientists Discover Unknown Organelle inside Our Cells

Scientists have identified a previously unknown organelle inside human cells, a finding that could lead to new approaches for treating serious inherited diseases, the journal Nature Communications reported.

This newly discovered structure, named the “hemifusome” by researchers at the University of Virginia School of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health, appears to play a crucial role in how cells organize, recycle, and dispose of internal cargo. According to the research team, understanding how the hemifusome functions may provide insight into what goes wrong in genetic conditions that interfere with these cellular processes.

“This is like discovering a new recycling center inside the cell,” said Seham Ebrahim, PhD, a researcher in UVA’s Department of Molecular Physiology and Biological Physics. “We think the hemifusome helps manage how cells package and process material, and when this goes wrong, it may contribute to diseases that affect many systems in the body.”

One disorder linked to such disruptions is Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome, a rare inherited condition that can cause albinism, visual impairments, respiratory problems, and difficulties with blood clotting. Improper handling of cellular cargo is a central issue in many similar disorders.

“We’re just beginning to understand how this new organelle fits into the bigger picture of cell health and disease,” Ebrahim said. “It’s exciting because finding something truly new inside cells is rare – and it gives us a whole new path to explore.”

Ebrahim and her team at UVA Health collaborated with Bechara Kachar, MD, along with Amirrasoul Tavakoli, PhD, and Shiqiong Hu, PhD, at the National Institutes of Health to identify the newly found organelle. The structure appears and disappears depending on the cell’s needs. To visualize it, the researchers used UVA’s advanced capabilities in cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET), a high-resolution imaging technique that captures cells in a near-native state by “freezing” them in time.

According to the scientists, hemifusomes assist in the creation of vesicles—small, blister-like structures that function as internal mixing chambers—and also support the assembly of larger organelles composed of multiple vesicles. This system is essential for sorting cellular contents, recycling materials, and removing waste.

“You can think of vesicles like little delivery trucks inside the cell,” said Ebrahim, of UVA’s Center for Membrane and Cell Physiology. “The hemifusome is like a loading dock where they connect and transfer cargo. It’s a step in the process we didn’t know existed.”

While the hemifusomes have escaped detection until now, the scientists say they are surprisingly common in certain parts of our cells. The researchers are eager to better understand their importance to proper cellular function and learn how problems with them could be contributing to disease. Such insights, they say, could lead to targeted treatments for a range of serious genetic disorders.

“This is just the beginning,” Ebrahim said. “Now that we know hemifusomes exist, we can start asking how they behave in healthy cells and what happens when things go wrong. That could lead us to new strategies for treating complex genetic diseases.”

4155/v