How Our Cellular ‘Antennas Affect Aging

Nearly every cell in our body has hair-like structures on their surfaces known as cilia. These tiny, thread-like organelles perform tasks akin to those of an antenna, detecting the flow and composition of nearby fluids and transmitting this data to the cell’s core. Consequently, they serve as a vital connection between cells and the environment, the journal Advanced Biology reported.

But besides their sensory functions, cilia also play a crucial role in embryonic development and maintaining the overall health of different organs. For example, when cilia are lost or malfunctioning, they can contribute to a wide range of congenital disorders and syndromes such as Joubert, Usher, or Kartagener syndrome, but also have been linked to many conditions that manifest later in life, including degenerative diseases in the central nervous system, like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s disease.

“If cilia do not work properly, many organ systems can be affected causing a wide range of diseases such as kidney cysts, sterility, obesity, blindness, among many others,” explained Melanie Philipp, head of the Department of Pharmacogenomics at the University of Tubingen in Germany.

However, contrary to conventional understanding, cilia’s influence does not stop at disease. Recent findings from a study, co-led by Philipp, have revealed surprising connections between cilia and aging.

For the first time, the team described changes in cilia morphology of the pancreas and kidney that naturally occur with aging. “Such changes have the potential to severely affect the function of cilia,” said Philipp.

This raises questions about the role of cilia in aging and opens up a new avenue of research into understanding the complexities of aging and its underlying mechanisms.

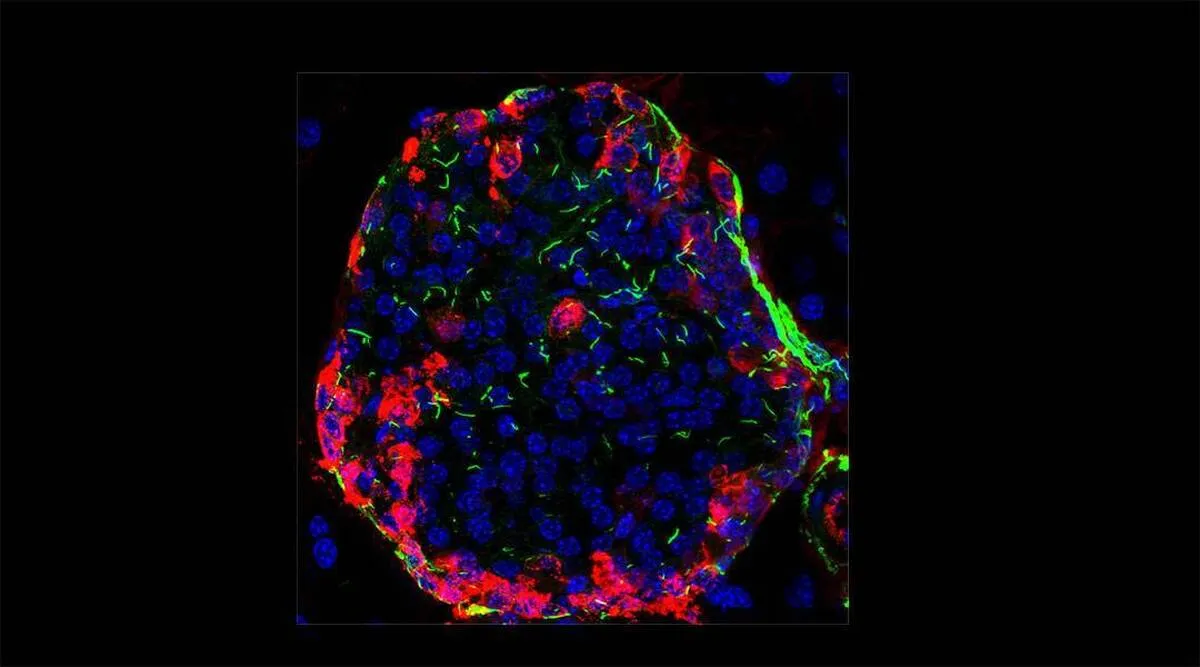

Philipp and the team took microscopic photographs of cilia in the pancreas and kidney from two-year-old and three-month-old mice. “We analyzed cilia in kidney and pancreas collected from very old mice,” said Philipp.

In both organs, cilia were found to be notably elongated compared to those in their younger counterparts. However, when studying their biological functions, there were surprises: the team studied the signaling pathways in the older cilia and found that different mechanisms were modified in the pancreas and kidney.

“It was intriguing that although cilia length increases in both aged kidney and pancreas, respectively, the influence on signal transmission and processing in the two organs differs,” said Martin Burkhalter, scientific assistant in the Department of Pharmacogenomics of the University of Tubingen and co-lead author of the study. “This indicates that kidney and pancreas have intrinsic differences that need to be analyzed.”

For example, when the researchers analyzed the amount of a protein known to be related to cellular aging called p21, they found higher levels of it in older kidney cells but not in the pancreas, suggesting that the elongation of cilia in the aging pancreas might not be directly linked to cellular aging while it could be in the kidneys.

Additionally, when the scientists measured the level of a protein associated with preventing cell death called Bcl2, they found it was regulated in the opposite way, indicating a higher risk of cell death in aging pancreas cells compared to aging kidneys. “Elongation of cilia does not predict the identical outcome for each organ or cell type,” commented Burkhalter.

The non-uniform results across organs add an intriguing layer of complexity to the research. While this may seem perplexing, it underscores the dynamic nature of scientific inquiry.

In the realm of science, investigations often provoke further questions: Could these elongated and dysfunctional cilia be contributing to the aging process? Are there ways to modulate cilia function to promote healthier aging? Why is cilia behavior different between the kidney and the pancreas? And how do they age in other organs?

This inherent curiosity is what fuels progress and innovation.

Although the experiments of this study were performed only in mice and the researchers do not know yet if cilia in humans behave in the same way, “the finding that cilia actually alter during aging is an important piece of information that may be potentially exploited,” said Burkhalter. This could be used to prevent or treat diseases.

“For example, elongated cilia in an aged kidney could cause dampening of a specific pathway, contributing to reduced kidney function. This could potentially be normalized by compounds that are already being studied,” he added.

Whereas further rigorous investigation is necessary before this becomes a practical application in clinical settings, the ongoing research offers a glimmer of hope that one day, this idea could turn into a real strategy used by doctors to help people lead longer, healthier lives.

4155/v