Scientists Find Most Important Thing to Restore Your Gut Health

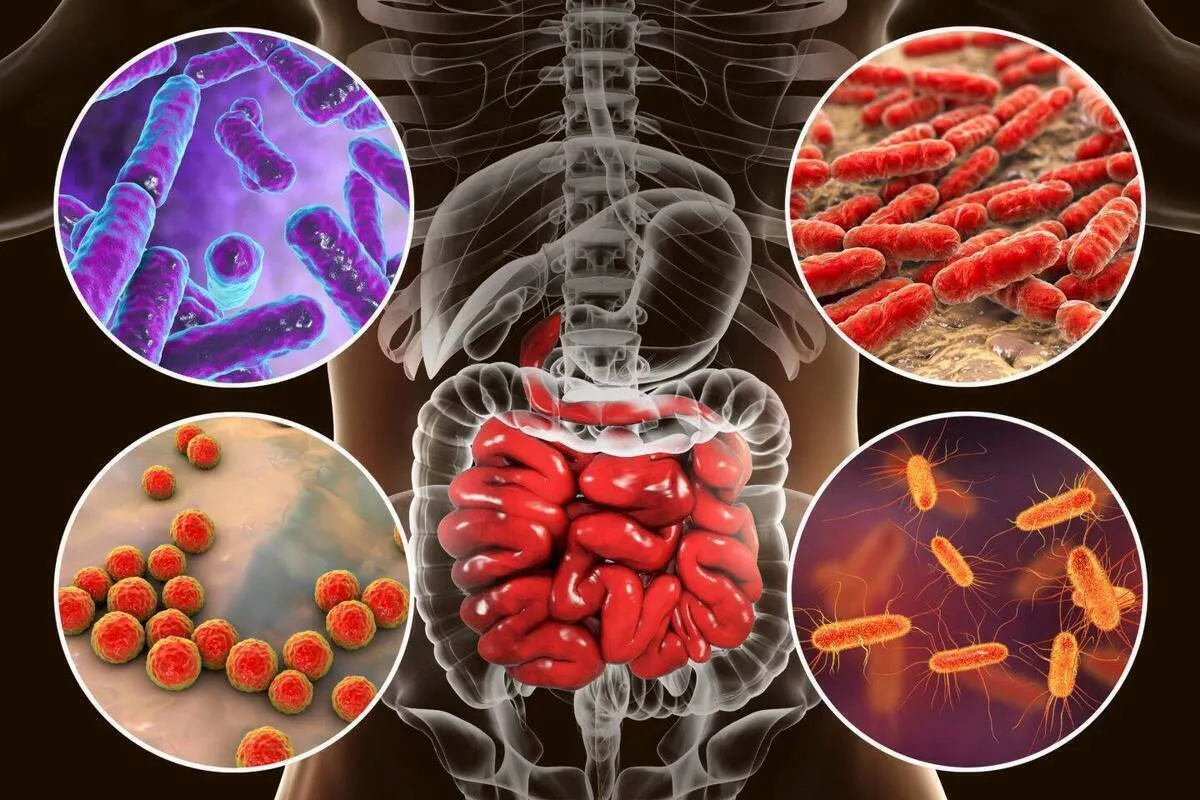

Trillions of microbes live in your body. Far from being harmful, most of these microorganisms form a diverse and vital community that supports digestion, boosts the immune system, and helps protect against harmful pathogens. When this microbial community is damaged or depleted, due to conditions like inflammatory bowel disease, antibiotic use, or bone marrow transplants, it becomes essential to restore it. According to a new study published in Nature, the most effective way of rebuilding the microbiome is also the simplest: maintaining a healthy diet.

“There’s a big emphasis on treating a depleted microbiome with things like fecal transplants right now, but our study shows that this will not be successful without a healthy diet, and in fact, a healthy diet alone still outperforms it,” says Joy Bergelson, executive vice president of the Simons Foundation’s Life Sciences division.

“This study is a great example of a clinically relevant finding that stems from very fundamental, basic science,” says Eugene Chang of the University of Chicago, who co-led the study with Bergelson. “It identifies a way of naturally restoring the microbiome in a way that’s easy, safe, and fast.”

The idea for the study emerged when Kennedy, the paper’s first author, was working on a project focused on improving recovery after antibiotic treatment. During her background research, she realized that one important factor was missing from our understanding of the recovery process: diet.

Many Americans follow a Western diet, which is typically low in fiber and high in fat. This type of diet is known to negatively affect the microbiome. Kennedy was surprised to find that few researchers were seriously examining how such a diet might influence a microbiome trying to recover after being depleted.

Working with her Ph.D. advisors, Chang and Bergelson, Kennedy set out to investigate. The team began with a straightforward experiment. Mice were fed either a diet designed to mimic a Western diet or a healthy, balanced diet for several weeks. Afterward, their microbiomes were wiped out, and the researchers tracked how well they recovered.

“In the mice that were on the healthy diet, within a week after antibiotic treatment, they recovered to almost their normal state,” says Kennedy. “By comparison, the microbiomes of the mice on the Western diet remained completely obliterated. They only had one type of bacteria left, and it dominated for weeks. They never really got back to the place they began.”

A diet high in simple sugars doesn’t support the development of a diverse microbial community. Normally, microbial ecosystems form through a sequential process: Some microbes first break down complex carbohydrates, producing byproducts that other organisms use to grow and thrive. This cycle repeats, creating a vibrant interconnected network of organisms that depend on one another to sustain their community.

In a Western diet, “the sugars are so simple to begin with that you don’t need somebody to come in and break down the complex ones,” says Bergelson. “So you get one organism that has a broad metabolic niche who can just come in and eat everything that’s there. It’s a much less rich community, and in turn, is not as versatile.”

The team then wondered whether diet would still have this same impact if a community of healthy microbes entered the body from a fecal microbiota transplant (FMT).

“The idea of an FMT is that you can take the good microbes from somebody who is healthy, plop them in, and that will fix them,” says Kennedy. “It has gotten a lot of enthusiasm, but we weren’t sure how it would interact with a Western-style diet.”

The answer? Badly.

“It totally doesn’t stick,” says Kennedy. “On a healthy diet, the transplant works, but on the unhealthy one, the mice show basically no signs of recovery.”

The results could shed light on the inconsistent clinical results of fecal transplants.

“Fecal transplants are rather hit or miss in practice: They work sometimes, and then they don’t work other times,” says Chang. “And maybe that’s because we haven’t been paying attention to diet.”

The researchers then turned their attention to the microbiome’s other job: defending against pathogens. Specifically, the team investigated invaders called ‘opportunistic pathogens’ that exploit a vulnerable system to wreak havoc. They wondered whether depleted microbiomes on unhealthy diets could be a prime target for these pathogens, and for how long.

The scientists again administered either Western-style or healthy diets to mice with depleted microbiomes. This time, they introduced an opportunistic pathogen — salmonella bacteria — two weeks after the mice’s microbiomes were wiped out.

“The mice on the Western diets get way sicker,” says Kennedy. “They lose a lot of weight and get awful diarrhea. Two weeks might sound short, but it’s the equivalent of months for humans. It just goes to show that these microbiomes are in a vulnerable state for an extended period.”

The clinical relevance of the study is clear: If your gut microbiome is in a fragile state, eating whole grains and greens could be the shortest route to health. However, the work also highlights ecological tenets that underlie many natural processes.

“Following a fire or a storm, what are the characteristics that help a system recover? How might you manage them to make them more resilient?” asks Bergelson. “These are big questions that take a long time to study on a macroscopic level. However, we can still learn lessons from smaller-scale studies like this one. Antibiotics are a much different kind of perturbation than, say, a volcano, but many of the same principles apply.”

4155/v