Low-Cost Contact Lenses to Tackle Color Blindness

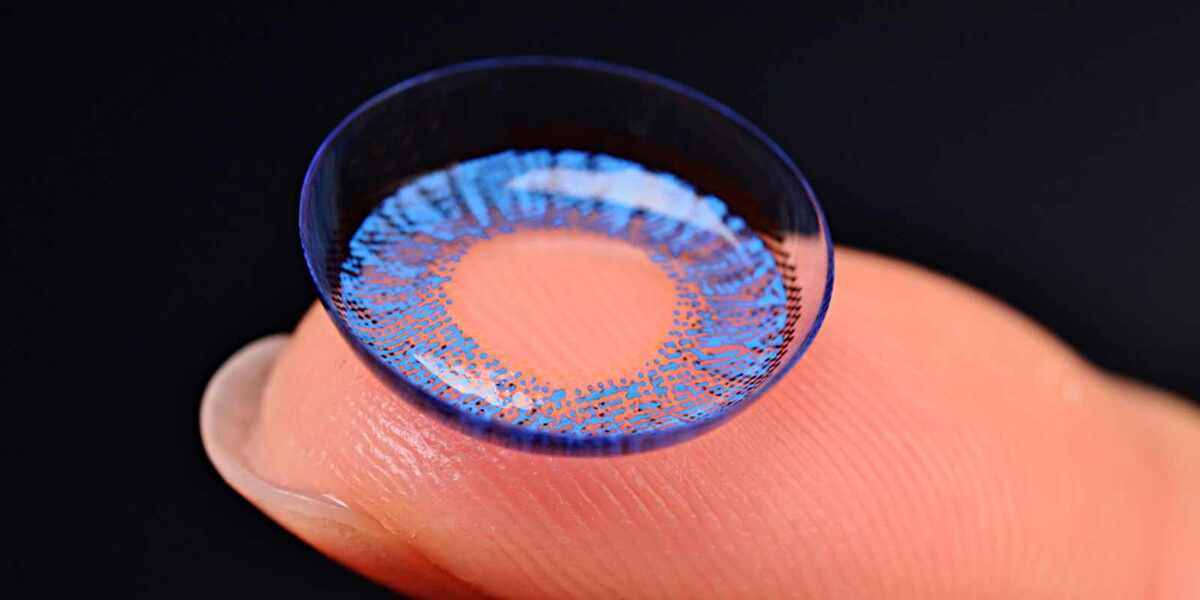

Imagine ordering a pair of contact lenses customized to fit the curvature of your eye. Now imagine that they also correct your color blindness. According to a recent study published in Macromolecular Materials and Engineering, this is not far from becoming a reality. Ahmed Salih, Haider Butt, and their collaborators at Khalifa University in the United Arab Emirates used advanced 3D printing and an economical dye to manufacture contact lenses that filter light to improve color blindness.

Color blindness is a hereditary condition with no cure that hinders people from distinguishing colors, shades, or brightness. It occurs in two out of every 100 people and is more frequent in men than women.

Everyday activities can be challenging as color blind people may have difficulties selecting food and clothes, identifying transport signals, and detecting changes in skin color, amongst others. This can also be difficult for certain professions that require color distinction, such as designer, pilot, or doctor.

Electromagnetic waves are the essential stimulus for color-based vision, but the eye does not respond to any wave, such as microwaves used for cooking or X-rays used in medical imaging; it specifically detects wavelengths of light that range from 400 to 700nm, which make up the visible spectrum.

With normal vision, the eye can observe the colors in the whole visible spectrum thanks to photoreceptors or cone cells. The human eye only has photoreceptors for blue (400 nm light), green (500 nm light), and red (700 nm light), while other colors are detected by a combination of two or more photoreceptors, such as red and green cones for perceiving yellow. In color-blind people, photoreceptors are either missing or defective, leading to an inability to observe certain colors or a distortion from what others would see.

As a strategy to manage color blindness, patients use tinted glasses or contact lenses that absorb light of specific wavelengths. “Blocking a range of wavelengths can help in color distinction by filtering out the problematic colors making patients see those colors in shades more perceivable for them,” explained Salih.

Although patients report improvements with these wearables, these modified glasses can be expensive and, in some cases, may still prevent some patients from passing color vision tests used to diagnose color blindness.

Due to these limitations, the team tried an alternative method to manufacture color blind contact lenses that maintain high quality and functionality but with decreased production costs.

To build the lens structure, the scientists used a mix of biocompatible materials that come together in a solid network that retains water called a hydrogel. They also added a pink ink that absorbs light in the problematic wavelengths for red-green color blindness — the most common form of color distortion.

To shape the lenses, the team used an advanced 3D-printing technology called mask stereolithography apparatus (MSLA) that produces high-quality data-x-items quickly and at low cost. “Compared with traditional contact lenses fabrication techniques (thermoforming and injection molding), 3D printing is relatively less tedious in terms of post processing, much more efficient in mass production, and allows simple customization of the lenses and to target […] several ophthalmic and medical diseases,” said Butt.

After printing, the team measured light transmission in the pink lenses and confirmed that they block light between 525 and 575nm — the range where the pink ink absorbs. Importantly, they demonstrated that the pink lenses preserve this light-filtering property over time, even when stored in water or contact lens solutions commonly used for disposable lenses.

Compared with a commercial model that also helps red-green color blindness, the pink lenses showed a similar dip in light transmission and water retention, but the key feature is that the pink ink is 700 times cheaper than the dye used in the commercial lenses.

The low cost is not the only benefit of the pink ink: it also improved the mechanical resistance and the lens’ surface wettability, which is the ability of a liquid to spread over a material’s surface. Better wettability avoids dehydration and build up of lipids and proteins from tears, which cause blurred vision and discomfort.

Lastly, the scientists tested the biosafety of the pink lenses, analyzing if they were toxic to human skin cells and if they had imperfections on the surface that could harm the eye. The lenses were non-toxic for cells in culture and were generally smooth, but some roughness remains at the contact points with the support structures used for printing.

Besides improving this, Salih indicated that “additional […] properties like oxygen permeability [how easy oxygen passes the lenses] and protein deposition [how much protein adheres to the lenses] need to be tested before conducting clinical trials.”

4155/v