Scientists Find ‘Off Switch’ for Cholesterol

By shutting this “off switch,” immune cells called macrophages regain their ability to soak up cholesterol, potentially stopping heart disease, diabetes, cancer, and more before they start, the journal Langmuir reported.

The team also fingered nitric oxide synthase as an accomplice, hinting at a two-pronged drug strategy that could revolutionize treatment for millions.

Researchers at the University of Texas at Arlington have uncovered an enzyme that works like an on-off switch for cholesterol control. The discovery could pave the way for new treatments that protect millions of people from heart disease, diabetes, and other inflammation-linked illnesses.

“We found that by blocking the enzyme IDO1, we are able to control the inflammation in immune cells called macrophages,” said Subhrangsu S. Mandal, lead author of a new peer-reviewed study and professor of chemistry at UT Arlington. “Inflammation is linked to so many conditions—everything from heart disease to cancer to diabetes to dementia. By better understanding IDO1 and how to block it, we have the potential to better control inflammation and restore proper cholesterol processing, stopping many of these diseases in their tracks.”

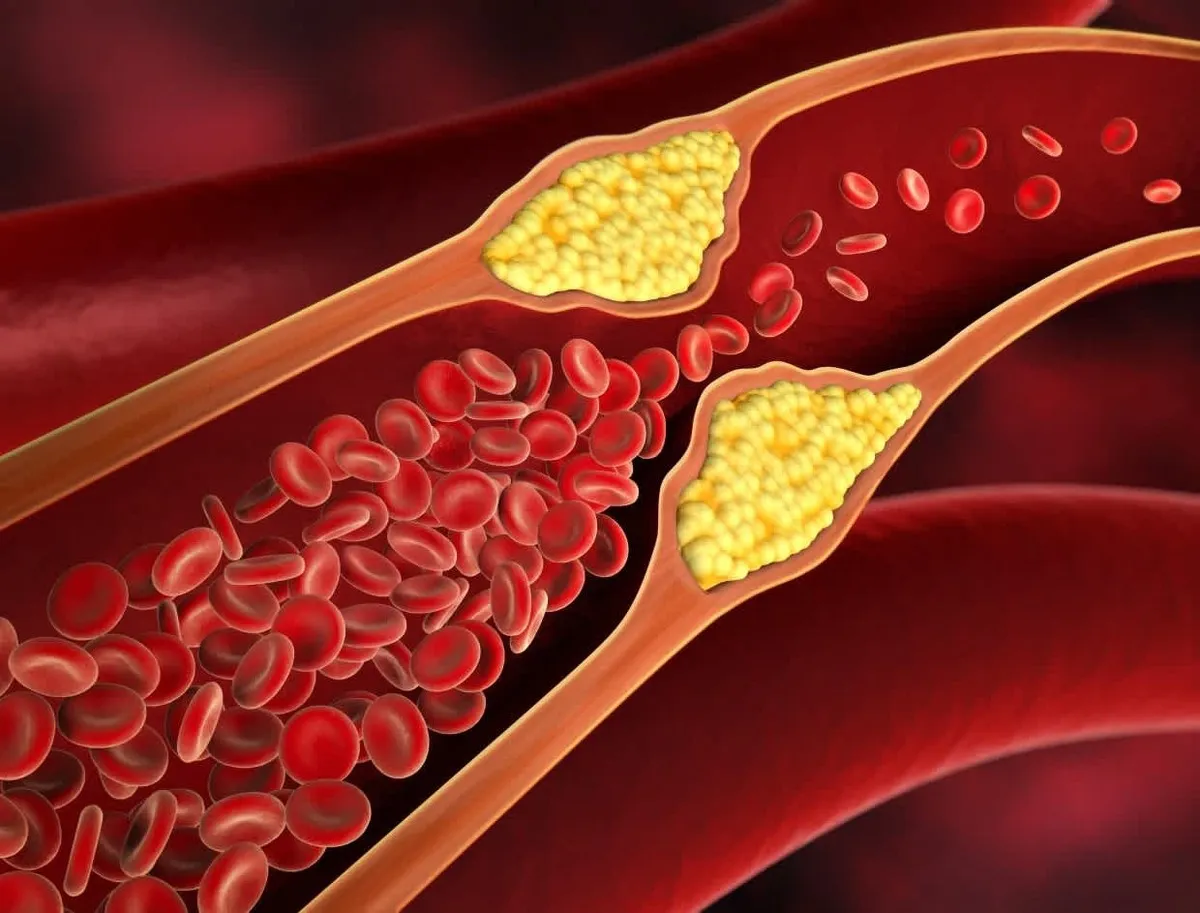

Inflammation is vital for fighting infections and healing injuries, but chronic inflammation caused by stress, injury, or infection can damage cells and upset the body’s balance. In these moments, macrophages struggle to absorb cholesterol, which raises the risk of serious disease.

The research team, which includes Dr. Mandal, postdoctoral researcher Avisankar Chini; doctoral students Prarthana Guha, Ashcharya Rishi and Nagashree Bhat; master’s student Angel Covarrubias; and undergraduate researchers Valeria Martinez, Lucine Devejian and Bao Nhi Nguyen, discovered that IDO1 switches on during inflammation and produces kynurenine, a molecule that interferes with cholesterol handling inside macrophages.

When the scientists blocked IDO1, the macrophages quickly regained their cholesterol-clearing power, hinting at a fresh strategy to prevent clogged arteries.

They also learned that another enzyme, nitric oxide synthase (NOS), makes IDO1’s harmful influence even worse. Targeting both enzymes could therefore offer a powerful two-step therapy for inflammation-driven cholesterol problems.

“These findings are important because we know too much cholesterol buildup in macrophages can lead to clogged arteries, heart disease, and a host of other illnesses,” Mandal said. “Understanding how to prevent the inflammation affecting cholesterol regulation could lead to new treatments for conditions like heart disease, diabetes, cancer, and others.”

Next, the research team plans to dig deeper into how IDO1 interacts with cholesterol regulation and whether other enzymes play a role. If they can find a safe way to block IDO1, it could open the door for more effective drugs to prevent inflammation-related diseases.

4155/v